From February 24-25h, 2018, the city of Marrakech, hosted the first Moroccan edition of the 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair, as well as the first event on the African continent. Both 1:54 Art Fairs, London, and New York, have been an annual event since 2013.

Marrakech’s iconic La Mamounia was the official 1:54 Art Fair venue, but many local art galleries, and art institutions around the city participated, adding to Marrakech’s already creative vibrant energy, with a new International Contemporary African Art Fair in town! [Public Program] 4000 local, and international visitors attended, 17 leading art galleries from Africa, and around the world, with over 50 artists participated in the 1:54 Art Fair.

The 9th edition of the FORUM, a parallel event held concurrently with the 1:54 Contemporary African Art Fair with a series of panel discussions, screenings, and performances happening around Marrakech. Morocco’s own, Omar Berrada was this year’s FORUM’s curator, hosting an event theme of, “unlearning of Eurocentrism”, and “forgetting about catching up with Europe” and focusing instead on “inventing new ways of acting and thinking.”

“Our world may be post-colonial, yet it has not been decolonised. Colonial powers may have left, but their past presence casts a long shadow, stubbornly occupying our mental, aesthetic and epistemic spaces. Everywhere colonial wounds lie wide open.

If decolonisation is another name for freedom, then it can only be unfinished business: a permanent horizon, never reached yet always longed for, as long as human life is structured by relations of race, class and gender domination. In the face of lingering coloniality, decolonisation is not a bygone historical event; it is an everyday task. Always decolonize!” [Always decolonize concept] Omar Berrada

"5 Artists - 4 Vignettes"

Mounir Fatmi, of Morocco

Conversation/interview conducted with Mounir’s gallerist. Website: http://www.mounirfatmi.com

FitWild: Can you tell me a bit about Mounir’s work?

Mounir is a photographer, but he also makes performances and movies. He’s from Morocco, he’s probably the most important photographer of Northern Africa at the moment.

FitWild: And these three pieces that we have in front of us—can we talk about the significance of these images?

In this case he’s talking about—this is a unique piece—he’s talking about personality. So we all have a sticker in our society with our name. In this case it’s written in Western characters and also in [the] Arabic language.

Society [expects] us to behave in a certain way. If you’re an artist, you have to behave in a certain way. If you’re a doctor, politician, singer…you have to behave in a certain way.

And [in this piece] he’s staring at that sticker, and he cannot recognize himself by what is written on the sticker. So at the end of the [series] he removes it because he cannot recognize himself in the stereotype that society wants him to be.

FitWild: I can also imagine working as an artist—having been born in Morocco and growing up in Morocco in the 1970’s—he had to transcend what was expected of him as a boy and adult as he became an artist.

Absolutely. He’s trying to break the conventions, and to run free as an artist should be.

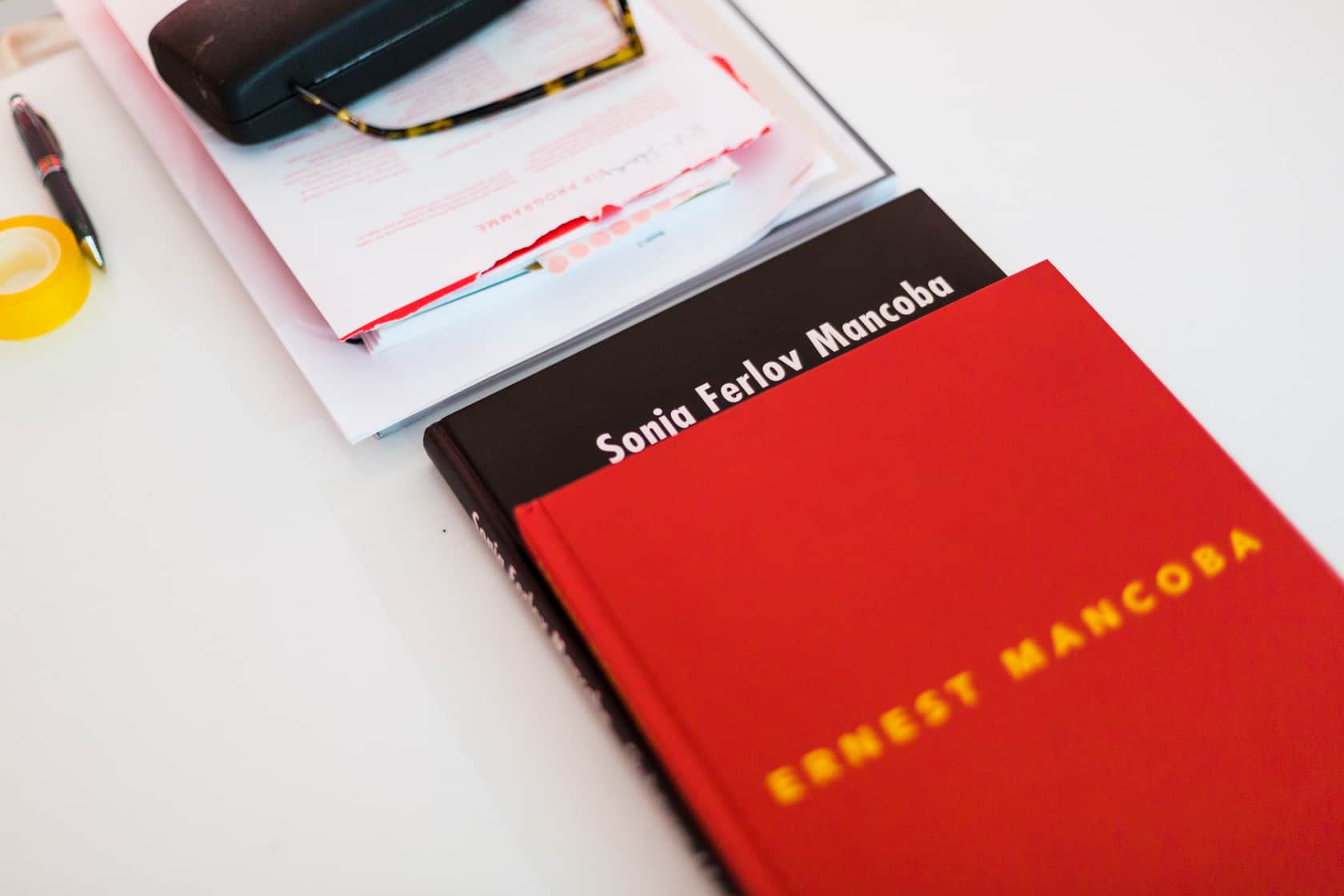

Interview: Gallery Mikael Andersen, Copenhagen

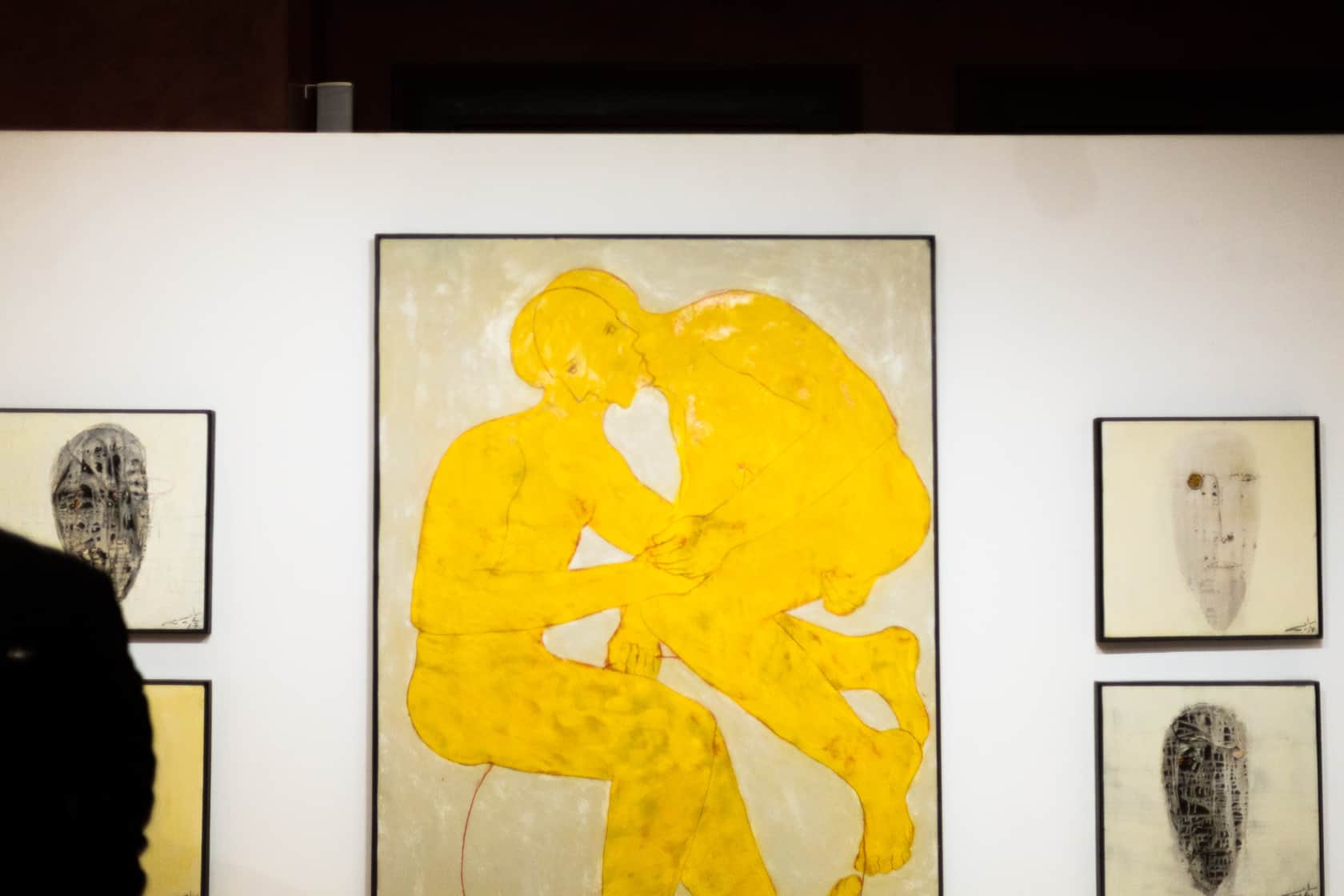

FitWild: In looking through Sonja’s sculpture works, humanity is very present. Can you tell me a little about her inspiration and motivations in what she created?

Sonja, of Denmark, was very much interested in the interaction between people…her art was not a political thing, it was more of a human thing. Like Ernest, [her husband] from South Africa, said, “a human being is nothing without another human being.”

And many of her sculptures of course work with this theme, humanity. The titles [of her work] also tell something about that. “A leap into the future”…”Solidarity”…her pieces are named like this.

And it has this human body [element] to it, but still it also goes either into African or Mayan kind of style[s.] So she also goes into tradition, and taking parts from other cultures, and sort of puts it into modernity.

FitWild: So her work is about interconnection between other cultures, but it’s also about connection with the past.

Yes. I think the past for her was very important. [She was] a European, whereas he [Ernest] was African; she came from the upper class in Denmark, and went down as a woman to become an artist.

Sonja and Ernest met in 1938 —an interracial couple—which was a big thing at the time. Ernest was taken by the Germans and put into a prison camp. They actually got married in 1942, in the prison camp; there was a German soldier who took a picture.

So, the contrast and the time when they lived influenced them a lot. but they sort of always spoke in “titles,” where he tried to find statements of what he thought was important in a modern life. So yes, humanity was something they really worked with.

Ouattara Watts, Ivory Coast

Interview: Sitor Senghor, representing the artist Ouattara Watts

Website: http://www.ouattarawatts.com

Website of Sitor Senghor, gallerist/curator: http://www.sitorsenghor.com/en/about-2/

FitWild: Can you tell me a bit about the relation between and the colors in these pieces?

They are watercolors in small format, and they were mainly produced for the Venice Biennale last year. He doesn’t usually do small formats. He’s used to painting in extremely large formats for a New York crowd.

He works in New York, even though he’s Ivorian, So, yes, he took this habit of very large formats….like, 4 meters by 6 meters. The smallest would be 1.5 meters by 1.5 meters.

He does smaller things, but not necessarily for sale; he does it randomly and you never have enough of them to organize an exhibition. So because of the Biennale he did more, and I managed to take some that were just in storage somewhere, to have a combination of enough works.

…and the colors are absolutely beautiful. I think that these smaller formats reflect more his personality than the large paintings. Because [with the smaller format] you concentrate on the subjects, and then they’re so…the watercolors are so well done that they’re smoother, they’re an invitation to get into the work.

FitWild: There’s definitely a theme of the human body present throughout Ouattara’s works.

The body is something important in African representation. So, you will see bodies or parts of bodies represented everywhere; and in Ouattara’s work, you will always see feet and eyes.

He paints feet because the foot is the symbol of the truth. Theres a saying on the Ivory Coast that you ‘don’t lie with your feet.’

The eye for him represents knowledge, the reading, seeing through things, going beyond. So there is a part of spirituality—a part of cosmic dimension—to what he does, and it’s told to us through these eyes.

[His work] is about seeking knowledge through the representation of things that are accessible to everyone. Everyone knows how a body is.

The following was written by Sitor Senghor, who is a collector and curator of Ouattara’s work. This was written to describe the collection being exhibited during the 2018 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair in Marrakech.

B O N P I E D | B O N ΠI L

Hale and hearty

(literally, good foot, good eye)

The eye, symbol of knowledge, desire and power, watches and sometimes judges. For some, the eye is hostile and harmful. In ancient Egypt, Horus’ eye, oudjat, offered protection against the evil eye. An amulet, a hideous mask, a talisman, a red thread, a fig, the khamsa… all offer protection against the evil eye. But the eye is also multiple, Mata Hari, the eye of the world, the eye of the heart, the third eye, the eye of the soul, a wink… the eye is for seeing although maybe, like for Tiresias, only blindness allow us to really see. More important, eyes must remain wide open to capture the beauty and the treasures of the world.

And the foot, firmly planted on the ground in order to stand upright. The footprint of Buddha teaches that the foot contains the entire body. The foot does not lie; it is the absolute truth. The representation of the vestigium pedis runs through Watt’s work. It is the origin of conscience, the flourish of inspiration, the source of life. You have to be barefoot to walk on sacred ground, to feel more rooted to the ground, to be part of the whole. Doesn’t having both feet on the ground avoid disillusion?

What if art could reconcile heaven and earth, reality and dreams? Feet grounded and eyes looking to the stars? My foot, says the skeptical. That’s wicked, responds the artist!

Sitor Senghor, February 2018

Kyle Meyer, USA

Interview: Kyle Meyer

Series Title: “Interwoven”

Website: https://www.thekylemeyer.com

FitWild: Kyle, the format of your pieces is unique. Can you tell me about about your creative process?

I received a grant to go to Swaziland, so it’s all made in Swaziland. It’s a tiny, little landlocked country in southern Africa. I went there on a grant to document the HIV epidemic; 1 in every 2.5 people are HIV positive. It’s the highest prevalence of HIV in the world. So, I’ve been trying to figure out why that specific place, why Swaziland.

So, I went there and I started working in factories. Most of the factories were making textiles, rugs, on looms, so that’s where the weaving comes from [in my work.] So I was apprenticing under several masters, learning how to weave, and during that time I was also documenting the workers.

So then, as a gay man, I started to explore the LGBT community within Swaziland. It’s illegal to be gay in Swaziland. I’ve been photographing [these men] since 2014. Each one of the men that you see here are all gay—so what I do is I take the fabric with me, and they choose whatever fabric they want, and I make the headwrap on them. Then, I take the photograph, which it then printed, and the fabric [which is woven into each piece] is the actual fabric from the headwrap.

It’s woven through. The headwrap is a part of their body, it’s a second skin that’s veiling them from societal oppression and the culture that they’re always hiding behind.

Fitwild: It sounds like a country that’s landlocked both literally and metaphorically.

It’s an extremely oppressive society, not only towards the LGBT community but also towards other ostracized communities within the country; albinos, for example. Women don’t really have many rights, it’s really hard for women to do anything without a male counterpart like their father or husband. It’s also a polygamist country, so a man can take as many wives as he wants, while the wife can only have one husband.

The headwrap is a signifier for femininity within the African continent, so really it’s so taboo for a man to wear this. They’d never be seen wearing a headwrap. So it’s about trying to push what gender means, and what masculinity is. Because some of them—this piece, for example—he’s wearing this headwrap and he’s got this mustache, but most people think it’s a woman just because of the signifier of the headwrap.

FitWild: How much time have you spent in Swaziland?

When I got the grant in 2009, I was there for two years; now I go at least once a year. I’m working on several different projects there…I have make sure that when I’m there, that I’m just working the entire time. I’m a person who has to be “go go go” all the time.

Fitwild: And what specifically drew you to produce these pieces?

So a lot of the men and women [in Swaziland], they can easily be denied simple health care. Basic human rights for the LGBT community are always pretty much denied. There are a lot of issues.

But it’s great that I have this platform—and my lovely gallerist, we’ve been working together for almost a year now—this is the first big showing of the work. And the reception’s been great, there’s always a worry about me being a white man making this very African art…without meeting me, most people think that I’m not white unless I tell them. So I feel very privileged that I’m able to tell their story, and everyone’s been so receptive. People are completely behind it.

Mainly, it’s about raising awareness for the issue. Unfortunately, these men have no platform. I feel very fortunate and I thank the universe—or whoever is guiding me at this point—that I’m able to tell their story.

The Next Edition of 1:54 Contemporary African Art Fair will be in Marrakech, March, 2019.

To Read More FitWild Adventures By Kirsten Kortebein – http://fitwild.wpengine.com/author/kirsten-kortebein

The next FitWild Adventure – Traveling to Papau New Guinea, “Forsaking the Next” by Sarah Fretwell