"Sharks are not attacking us because they want us dead, sashimi and juicy. Sharks do not feed on humans"

Accidents due to sharks are on the rise. That is a reality marine biologists from across the globe now agree on. They also agree on the fact that using the term “attack” is deeply inaccurate: sharks do not feed on us and, more importantly, sharks can most probably and most generally tell the difference between a tasteful sea lion fattie, a bleeding desperate fish and a healthy human being. Just like any stray dog in the world will tell the difference between a legit T-bone steak and an careless runner’s calf. As a surfer, swimmer and scuba diver myself, and as an advocate for face to face arguments, I decided to head for a serious conversation with those so-called dangerous creatures. And for this, I went to Tahiti, a relative safe heaven when it comes to swimming with sharks.

Text by Gaël Couturier. Underwater photos by Top Dive, Cyril Dumont, Greg Le Coeur, Sylvain Girardot, Philippe Joachim, Vincent Truchet.

It all started when I read a gripping article in the April issue of Surfer magazine called Safety not guaranteed, by Justin Housman. The story discussed an alarming increase of shark attacks on surfers and their bodyboarders, bodysurfers, scuba divers and other ocean swimmers’ friends who have a terrible and now self-destructive tendency to consider it a limitless joyful risk-free playground that belongs to them and to them only. It’s as if infamous localism was not only directed at other surfers but at the very inhabitants of the ocean. How ridiculous.

Mid-July 2015, 3-times World Champion Australian Mick Fanning had a very close call with a great white shark, during Jeffreys Bay’s World Tour competition in South Africa. The shark, apparently, went for the board instead of the human flesh, probably saving the life of the professional waterman. Fanning escaped, unarmed but shocked. And so were we. I believe it was the first time ever that a well-known pro surfer had met such a close call with a shark during a live World Tour competition, both on TV and on the Internet.

Sadly, the Surfer magazine’s story was premonitory. As I’m writing this, today, April 30th, a young woman identified as Leeanne Ericson has been bitten at the San Onofre State Beach in Southern California, a coastline known for hosting one of the largest great white shark population in the world as well literally being a giant nursery for them. This poor woman, a single mother of three, is now fighting for her life at the hospital.

We, as ocean lovers and beachgoers, have all heard or read of shark stories, been directly or indirectly involved in one. As a summer break surfer of North Carolina’s line-ups, I remember a friend’s board, proudly exposed on a living room wall of a Wilmington townhouse. Mr shark had struck the board while our friend was peacefully waiting for a wave, taking a bite between his tights and his hands before deciding that he was not liking it, letting our friend live and gently swimming away. No blood was spilled this time, no lifeguards, ambulance and helicopter were involved. It was just a matter of adrenaline, fear and a broken board. I spent many summers surfing in North Carolina, surfing the same places as this friend did, the same beach breaks, at same time of the day or year, and probably with the exact same curious shark male or female around and below us.

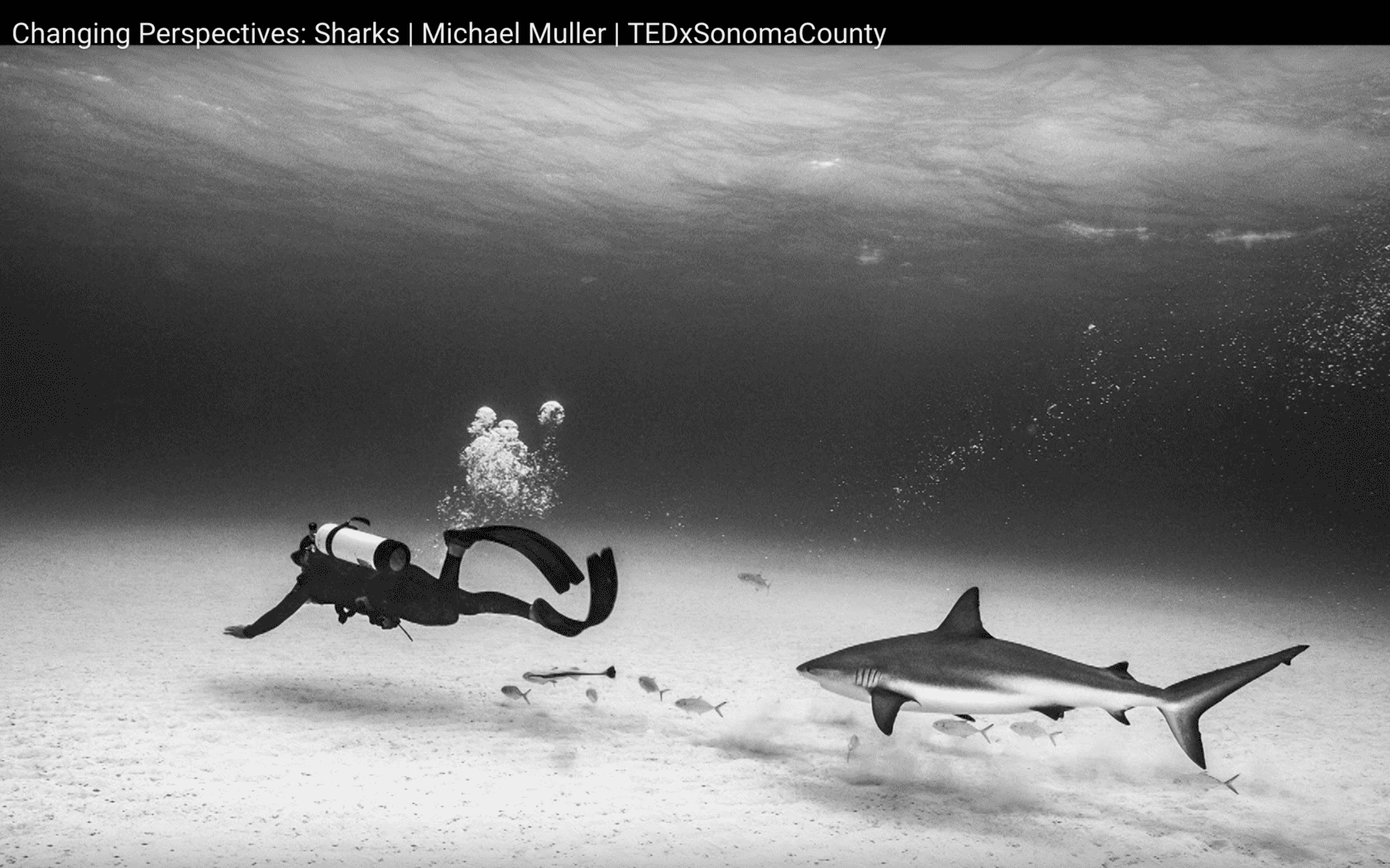

South Africa, North Carolina, California, Florida, Hawaii, Australia, Africa…you name it. All over the globe, it may look like we are underwater attacks. Statistics about accidental sharks encounters with us, the surfers, the swimmers, the scuba divers are indeed on the rise. That is a reality all marine biologists agree on. What makes sharks hit us? The scientific community comes up with the best answers: defense mechanisms – some people are so stupid that they sometimes harass sharks for fun and get bitten – and simple, sad, animal error. All this means that sharks are not targeting humans for feeding. They are not biting us because they want us dead, sashimi and juicy. They bite us because they are as afraid as we are and as territorials as we are. Except they’re stronger. We happen to venture in their environment and, since those are ferocious predators we’re talking about, they just behave like ones. Hello! Like this photographer, Michael Muller, who spent 10 years swimming with all kinds of sharks, from 16-foot tiger sharks, bull sharks or, great white sharks, puts it in Changing Perspectives: Sharks, a TEDx recorded in Sonoma county: “How many of them do you think we’re killing? A hundred million a year. How many of us they’re killing? Five”.

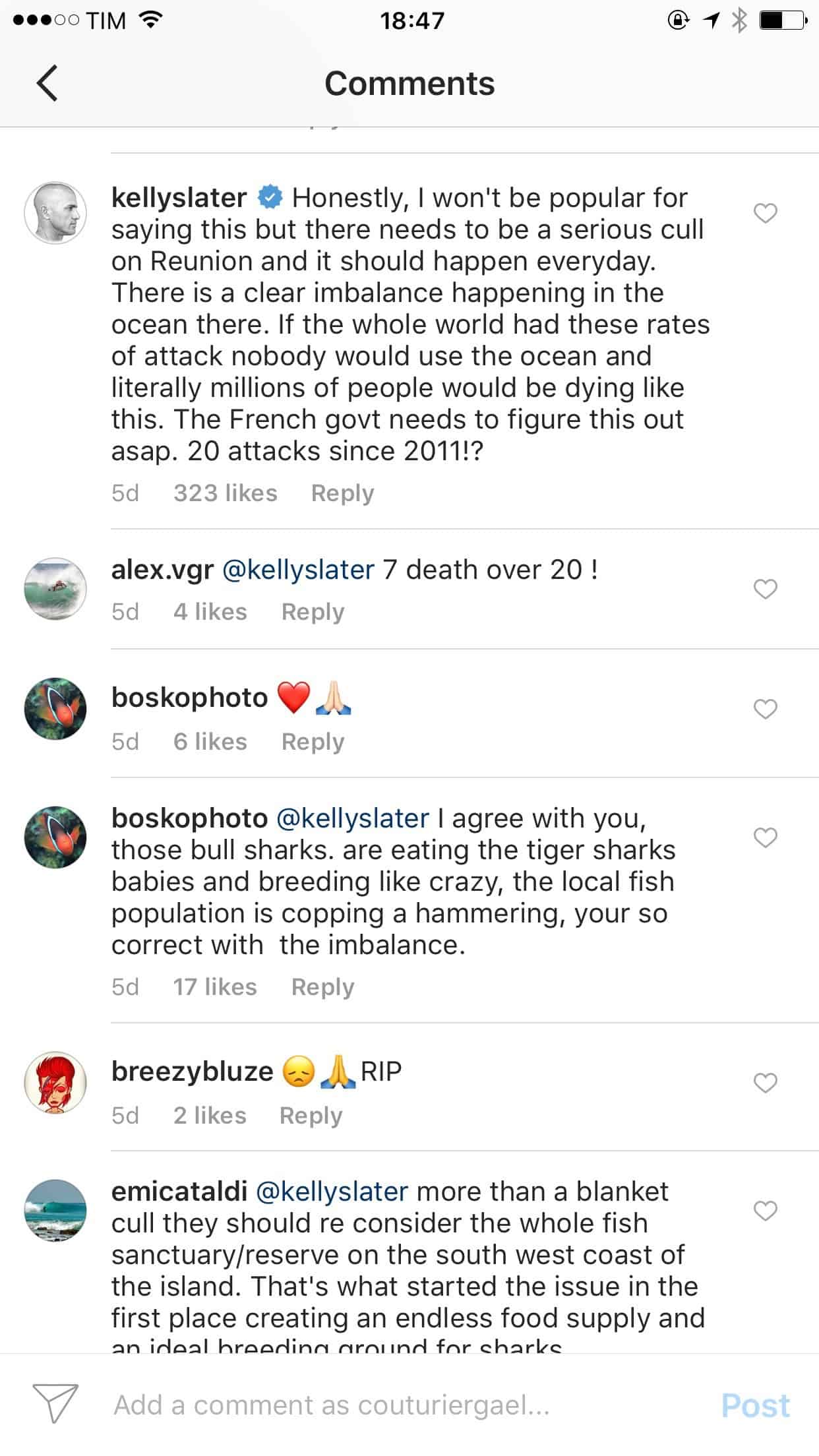

Last February, on Instagram, a handful of innocent and naive pro surfers, at best, selfish and uneducated, at worst, including 11-times world champ’ American Kelly Slater and French star Jeremy Flores, called indeed for an everyday cull – a massacre really – on sharks inside the Reunion island waters, East side of Africa, by Madagascar. Alexandre Naussance, a young bodyboarder had died the day before, from blood loss following, what was believed to be a bull shark bite. Passion and emotions overruled common sense, cold blood thoughts and again, education. To some researchers and marine environmentalists, culling, or any other artificial ways to make the oceans a safer place for humans for that matter, are not the right way to deal with sharks and their white smiles, spontaneous personalities and natural born killer instincts. A quick check on social media will convince you that the debate is on and definitely hot as Adrien Dubosc, another bodyboarder and local well-known shark advocate, died just a few days ago as a result of his injuries after another bull shark bite, making it the ninth fatal encounter over six year in the Reunion island. If I can put it that way, that’s 1,5 dead person a year.

What really appears to be the most modern and intelligent solution to those “attacks” is a change of behavior from the humans, not from the sharks. Dr Chris Lowe, the director of the Shark Lab at California State University Long Beach clearly stated it in a recent TEDx talk called Bringing sharks back from the brink : “We’ve spent a lot of energy and money in order to bring those predators back and we have done a lot in terms of educating the public about their importance. We don’t want to go backwards. What we have to do is become predator educated, so that we can all be safe when we use the ocean. It’s their home. We’re visitors. We have to learn to share the waves”. I know haters will wish me death-by-jaws for saying so but I think this man is right: we can’t turn the oceans into a slaughterhouse again just because a few daring, and often incautious, humans have been…bitten.

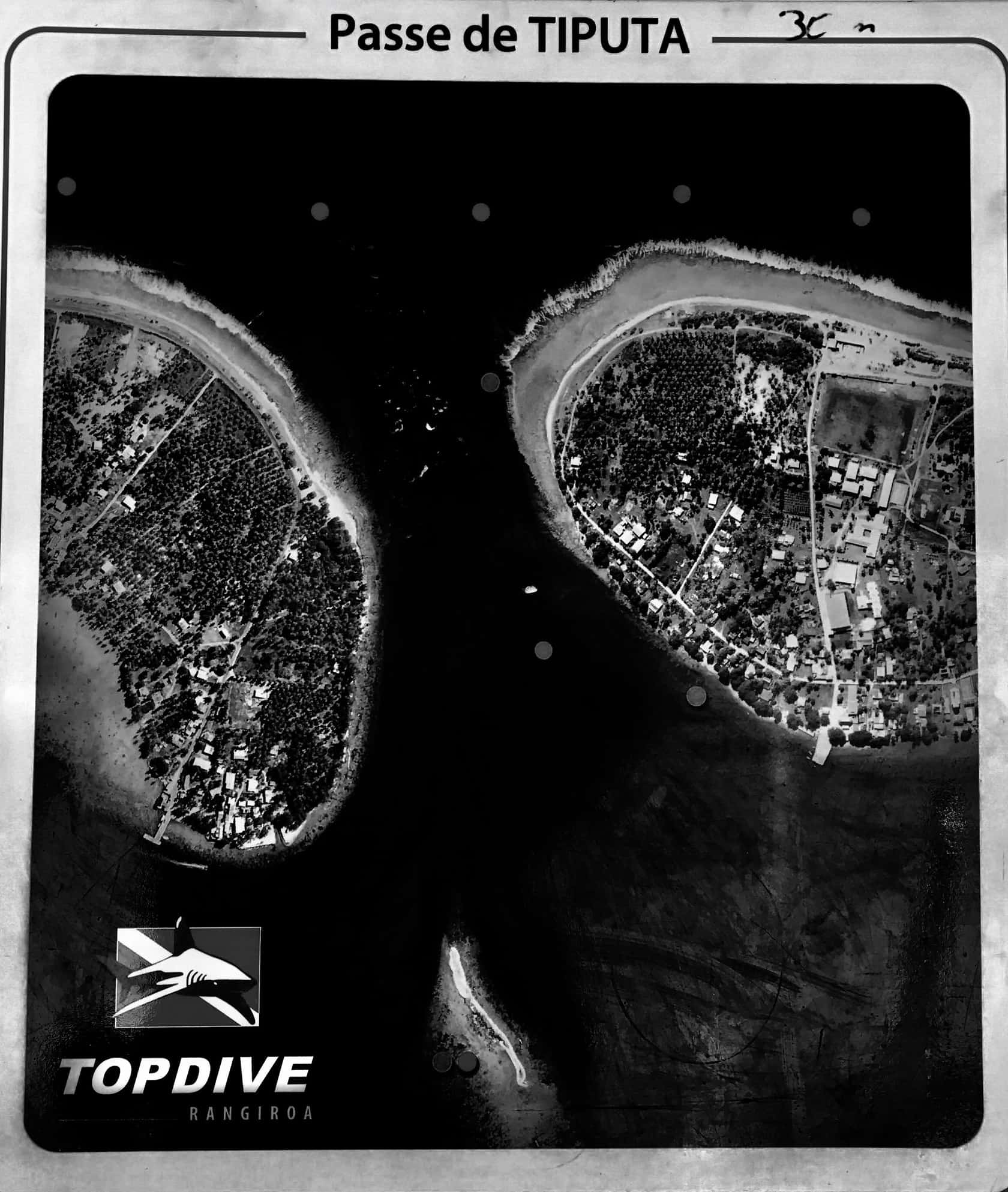

In order to change my belief system on sharks, pretty much set since kindergarden (thank you Steven Spielberg), and because I love scuba and I am passionate about adventure sports, I embarked on a mission to finally see clear in this ugly mess made out of human flesh, salty blood bath and great white teeth. I decided to take an action oriented approach and head for a a place where sharks and human have always managed to live together peacefully, as far as we know it at least and because, well, you know, I’m not suicidal. It is a place where tattooed natives are known for respecting the ocean and whichever gods of their marine creatures live in it. It is where humans and predators have been able to share a hunting territory with respect for one another, sometimes even playing fetch together…well, O.K…may be not playing fetch. I was heading to Tahiti in order to dive with sharks and see if I could wisely participate in a fun feeding frenzy shark session right outside Papeete reef breaks where my fellow surfers enjoy some of the best barrels in the world. But before that, I sure needed a refreshing scuba diving course as well as a soft introduction to swimming with sharks. My first stop was Rangiroa, the largest atoll in the Tuamotus, and one of the largest in the world, about 355 km northeast of Tahiti, French Polynesia.

Rangiroa is an amazing place. It is remote, quiet and there’s not much to do there besides dive, eat, sleep, repeat. I was based out of a hotel on the beach, small, family oriented, peaceful and with one of the smallest and pretties wooden jetty I had ever seen in my entire life (rangiroa.hotelmaitai.com). On the day of my arrival, as I was lying down on its bench for a short outdoor nap, trying to cope with the most violent jet lag ever, a young tourist couple with a kid walked by. They sat down on the side of the jetty, legs hanging on the air, feet a few inches from the water surface. Their 5 or 6 years old kid imitated his parents. Because of his short legs, his cute baby feet hanged a little higher from the surface. They had brought some bread from the restaurant and were throwing pieces into some of the clearer ocean water I have ever seen. Immediately, within seconds, dozens of hungry colorful fishes coming from out of nowhere swam by, feasting on the french bread with hysteria. “Oh look at the little shark!” softly said the mother to her husband and the kid. A 5-foot grey reef shark was attending the meal too, hoping something bigger would fall in the water I supposed, like…a six year old human baby leg or hand, or finger, may be? The moment has some elegance. Everyone involved was calm, but me. What if the little shark jumped out to hit the kid and dragged him under water forever? I was definitely not going the follow. Parents, hotel managers, baby human and baby sharks, everyone was sharing the space, enjoying the moment. No one was panicking. But me. How was that even possible? I had to calm down. I had to understand. I had to dive. The shark was so beautiful, silent, agile. And deadly.

I'm an air pig.

The next morning, I was given a spectacular show. As soon as I hit the water with the other divers, I see them. Sharks are everywhere. And they’re bigger than the baby one from yesterday.

*Swimming with Sharks – part 2 coming soon!

*Read more FitWild Stories by Gael Couturier here, http://fitwild.wpengine.com/author/gael-couturier