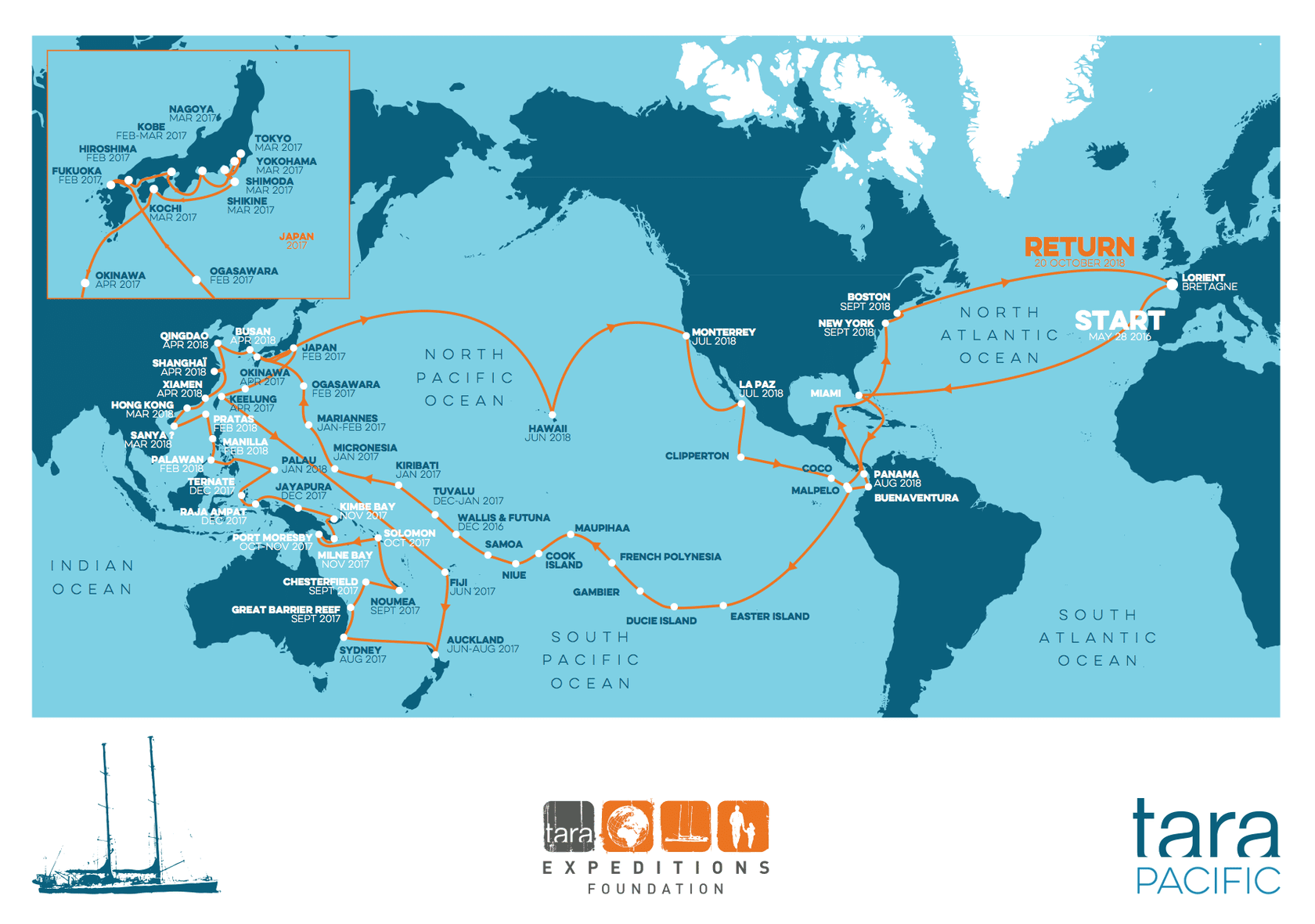

4,000 nautical miles, + 62 days, + 6 countries, + 1 legendary research schooner = Tara Expeditions adventures in the name of science

Multimedia storyteller Sarah Fretwell’s journey with Tara Expeditions Foundation across the Pacific researching the fate of coral ecosystems in the context of climate change.

Three years ago, I met a French girl on a balcony in Bali. Little did I know, meeting this one person would ultimately send me on the journey of a lifetime. Now, I am sitting on the bow of the 118-ft. Tara Expedition s schooner, cross-legged with my hands in “Gyan Mudra”, as dawn breaks over the atoll of Abiang in Kiribati – enjoying my only moments of peace during the day. I take in my surroundings one more time before I close my eyes to meditate: “I am so grateful that I am alive in this time. I am so grateful to have the opportunity to work on stories important to the planet. I am so grateful for all the beauty around me. I am so grateful to be here.”

“Two years ago, I randomly cut out a photo of some islands in the Pacific and pasted the image on my vision board, next to a photo of surf adventurer Liz Clark on her sailboat “Swell.” At the time, I didn’t know the name of these islands and my only thought was that I would really need a boat if I was going to go there. Now, I interviewed the Prime Minister of Tuvalu 5 days ago. And today, I will visit a remote atoll in Kiribati (pronounced kirəˈbäs) to hunt octopus with local fishermen.”

“And, when you want something, all the universe conspires in helping you to achieve it.”

― Paulo Coelho, The Alchemist

As an athlete, adventure traveler, and multimedia journalist, pushing the limits of my body, heart, mind, and spirit has become my way of life. While at times my existence is a “baptism by fire,” there are also many moments when everything is flowing. Whereas I am so alive and life is so rich that I cannot go back to “white picket fence living” as my life coach calls it. My formula has been this: Dare to dream, write down or vision board what I want, surrender the “how” it will happen, follow the path that unfolds with childlike curiosity, and say “YES.” Serendipitously, it all landed me here as the on-board correspondent for Tara Expeditions Foundation for two months of her epic two-year, pan-Pacific coral reef study, looking at the fate of Pacific coral reef ecosystems in the context of climate change. This expedition is a scientific first in that a study covering such a large geographical area – over 62,000 miles in the Pacific Ocean where 40% of the planet’s coral reefs live – has never been accomplished. As Tara Expeditions Foundation puts it, “The unique nature of this expedition is its global approach, offering us the chance to establish an inventory on a spatial scale never before apprehended.”

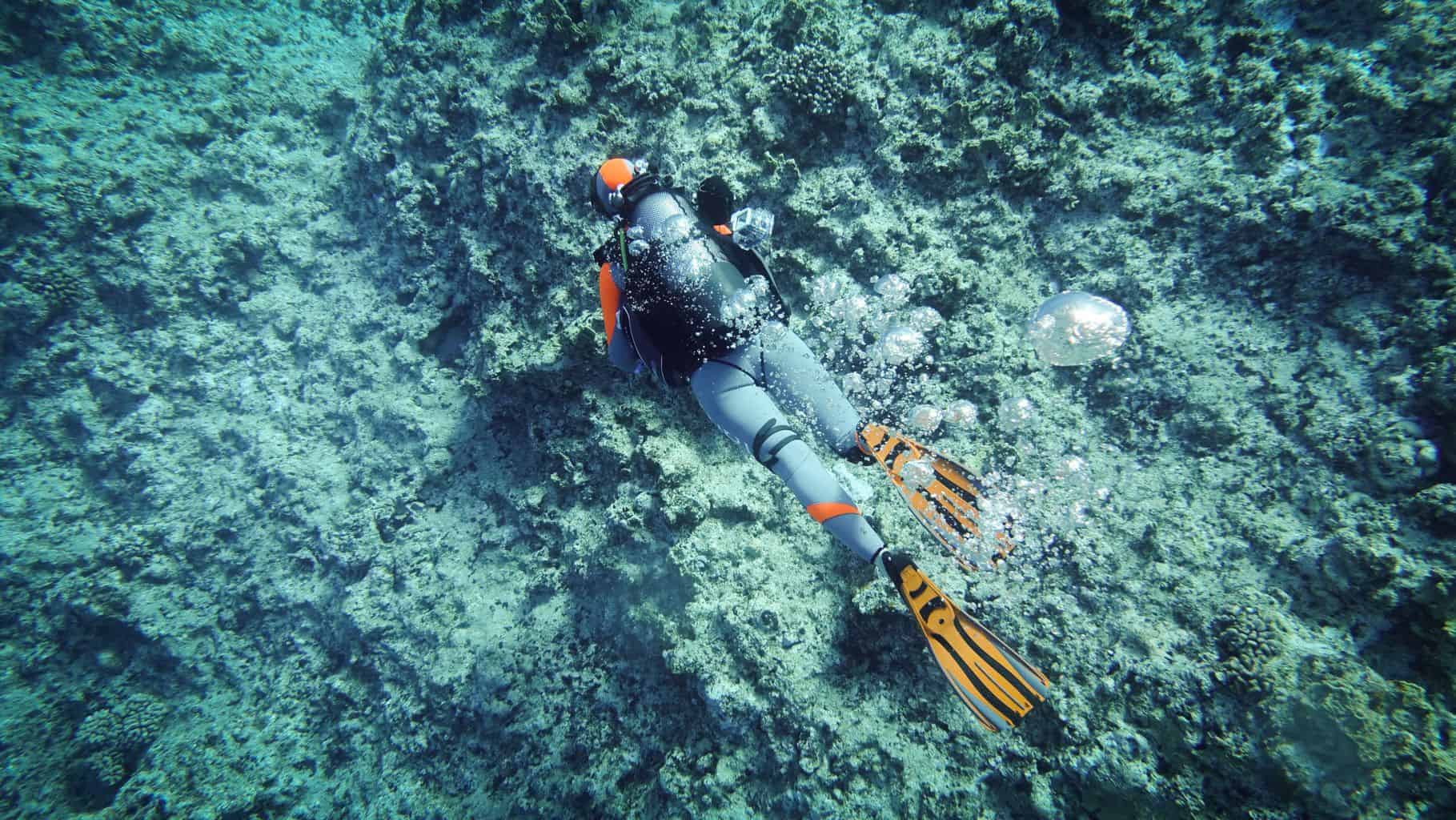

Threatened by global warming and ocean acidification, coral reefs play a crucial role both ecologically and economically . Given their extreme sensitivity to changes in the environment, they are good indicators of the ocean’s state of health. For Tara Expeditions, studying coral means alerting as many people as possible about the many environmental challenges that today affect the ocean, a key ecosystem for humanity.

– Tara Expeditions Foundation

Spanning six countries in two months, I am aboard for the countries of Wallis/Futuna, Tuvalu, Kiribati, Chuuk, Guam, Orgasarwa (Japan), and Fukuoka (mainland Japan). With a French crew of five (a few of them smoking vegetarians), seven international scientists, one Aussi underwater cinematographer, and me, the lone American. With a remorseful smile, I immediately clarify for everyone I meet, “I didn’t vote for Trump.” The seasoned crew is a mostly a tight-knit group of “Taranauts” who have worked all around the globe and on past Tara expeditions. The scientists (many of whom are aboard for the first time) are broken into teams – the coral team, the fish team, and the plankton team. An “international boat,” I am the first non-Francophone correspondent ever aboard. I am not fluent in French, yet my job position offers me a lot of autonomy and responsibility. The expedition is timely in that between 2014 and 2016 our planet’s oceans experienced the longest global bleaching events ever. Why does this matter to you?

Aboard “the schooner for the planet” my job is to disseminate the science and discovery taking place in real time. My focus is the challenges facing coral reefs (bleaching and ocean acidification), environmental issues (like overfishing and improper disposal of toxic waste) compounding the situation, human impact on the environment and the resulting impact on human lives – all in the context of climate change.

The reality of my job means I am simultaneously navigating life within two others cultures (French and whatever country we are in at the time), discovering how to live on a boat, learning the “protocol” for the Tara correspondent position, trying not to be intimidated by my highly accomplished cohorts (whose area of expertise are admittedly not mine and whose findings I must report on in an intelligible way), getting schooled by the science and jargon of coral reef ecosystems, getting doubly schooled in the culture of the foundation, and producing high-quality media content at neck-breaking speed.

In my job position, I write two articles a week, provide daily photos and updates, and direct/shoot/edit a video project in each location, as well as shoot specific projects for French television and Japanese television, handle photo requests for our media partners like Walt Disney Company France, Tara education partners, and field other requests that spring up every other day along the way. The correspondent before me also seamlessly shot two feature documentaries on top of his Tara workload – a tough act to follow.

Tara, is a polar schooner whose every inch is dedicated to science and serves as a floating laboratory . In addition to our 24-hour-a-day/7-day-a week “jobs”, we alternate between cleaning the toilets and showers, serving dinner, washing dishes, and serving lunch. While we are under navigation, the crew members are on four-hour watches overnight, and the rest of us wake up for two-hour shifts between midnight and 6am every third night. There is no such thing on this boat as “that is not my job.” Anything that needs to happen to make the boat function smoothly – and ultimately the expedition succeed – is what is expected of everyone aboard.

My 2’ x 8’ bunk bed berth is the only place I have to decompress and get some alone time. Surprisingly, my coffin shaped bunk and small fan feels luxuriously comfortable at the end of the day. One evening, I wake up in the middle of a muggy tropical night, falling out of the top bunk as we crash forward against waves, to see a waterfall of saltwater raining down on top of my bunkmate because our sole hatch has not been secured properly – all we can do is laugh. This happens two more times during our voyage and each time the nighttime dousing of salt water is met with less and less humor.

I have many moments of sheer revelry where I cannot believe the amazing adventures and array of my skills my job involves. Heading to “work” on the Tara dinghy with scientists to video them collecting plankton samples, photographing the fish team underwater as they spearfish for samples, night watch under star filled skies, and jumping off the boat into 4,000 meters of crystal clear tropical water in the middle of nowhere, days from land.

Other moments, the truth of my reality aboard the “polar schooner” is hours drenched in sweat, sticky with the humidity of tropical heat, with a metallic taste of sea sickness in my mouth. I am brain-fogged and nauseous, as I try to meet cranking deadlines from my office in the sauna-like conditions of “PC com,” the captain’s office. It takes all my focus to work during the endless crashing of three to five meter waves. Once we start moving at full speed, it is perpetual motion for the next 7 days. The conversation with myself in my head goes something like this: “How many days have we been underway? Two? Three?” It is hard to tell. The days all blur together. It’s hot. Stifling hot.

As our schooner insulated for comfort on an Arctic ice drift blazes across the heart of the equator, the wheelhouse temperature gauge reaches 120 degrees fahrenheit.

Life aboard is a series of making a plan – and always having the plan change. We never know when the customs and immigration people will show up to give us clearance into a country. In typical “Pacific” style, they often take their sweet time. In each location, if we arrive on a Thursday, we may have to sit in the harbor captive on the boat until Monday. Many islands in the Pacific seem to have a three day weekend, every weekend. Sometimes, officials don’t answer the radio call, or leave us just sitting there for 24 hours, unable to leave the boat until we have legally entered the country. Often my story assignment is far away from the sample sites, so I go ashore for one to three nights, armed with my photo and video gear shrouded in black Tara drybags and a VHF radio to contact the boat in case of emergency.

We never know when things will happen for sure so the plan is always in flux – but when they do happen, they happen quickly. You should always be ready early so no one has to wait around for you. If the crew says the boat is leaving at 2pm, that means the engine turns on at 1:45pm. I am pretty sure they would wait for me, but I decide to never test the theory.

*Lead image photo: Tara under way off of Teirio Atollm Kiribati. ©Niko De La Brosse/Tara Expeditions Foundation.

TARA Expeditions – Part II To be continued.

Important Links:

Tara website: http://oceans.taraexpeditions.org/en/

Follow the journey on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/tara.expeditions/